Exciting news: I have released an audio version of this post via Substack as well.

For that, visit the “podcast” tab.

In a time of media over-saturation, too much screen time, and too many opinions, I find myself craving direct contact with real people, face-to-face. I need tactile experiences like meals together and weekends spent making crafts and chatting and listening to records. I look forward to warm nights on the back porch with my friends, sorting out our increasingly difficult inner worlds, laughing together, and connecting. My hobbies are often solitary: art making, gardening, writing, bookmaking. I am quite introverted, sure, but I want these hobbies to connect me with others too.

This is part of why I started this project (Fox Hollow) in the first place. It is restorative to read newsletters and blogs of other people making art and growing food in sustainable and regenerative ways, learning about the power of native species in ecosystems, learning how to forage food, and connecting with flora and fauna where they live. I see it both on the internet and in real life. In these increasingly difficult times, it’s a powerful thing to connect with others working toward a better world.

Gardening is one method of bringing people together for a tactile experience— to learn, to practice, to labor together. Another is artmaking. I’ve been making art nearly forever in one form or another, from childhood pastel sets to an undergraduate degree in studio art, to making prints by hand at home. Through my undergrad degree wasn’t technically focused in one area of artmaking (a B.A., not a B.F.A), I purposefully sought out as many printmaking and bookmaking classes as possible. It felt natural and it was (is) an absolute refuge for me. I learned to bind books by hand, combine handmade prints into those books, and explored so many different mediums, methods of binding, and experimented with countless printmaking techniques.

I was making hand printed and bound books in various shapes and sizes, filled with poems, illustrations, and various ideas and convictions at the forefront of my early-twenties mind. Artist books are sometimes funny, sometimes purely aesthetic, and sometimes expressive of an idea or concept. Though I was hovering so close to zine-making, I wasn’t all that familiar with the term. I only knew they were often associated with the riot grrrl movement of the 90’s. As it turns out, there’s much more to them than just that.

What is a zine?

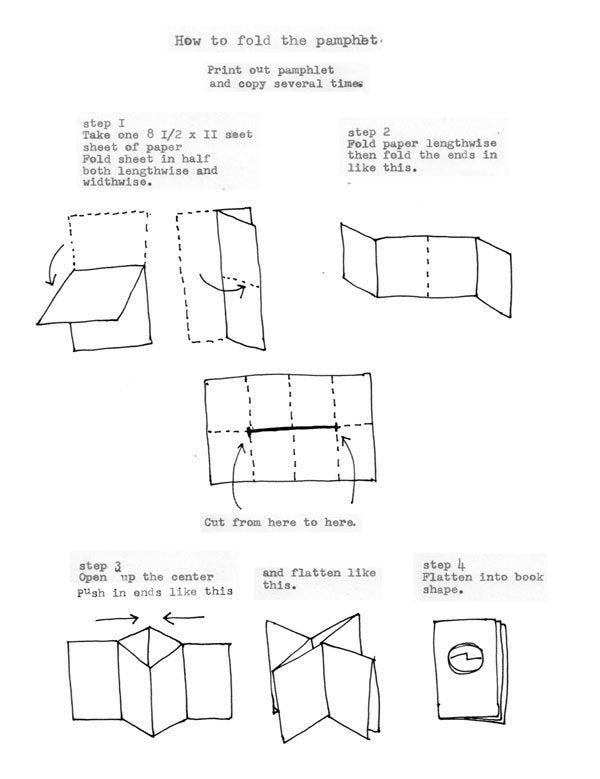

A shortened version of the word “magazine,” zines elude formal definitions and categorization. They are handmade, self or independently published, and combine written words with images, but do not advertise or try to sell you products like magazines do. They usually aim to teach, share, or entertain, and have a DIY look about them.

Zines promote learning and community, providing information or entertainment for free or at a very low cost. They’re often illustrated and aim to meet a certain look, anywhere from “ugly” punk rock aesthetic to delicate, detailed illustrations and everything in between. Zines are not commercially produced, but are printed in small numbers in a very cost-effective way. People trade zines or charge a low amount like five, maybe ten dollars at most. Hyper locality is a unique quality of these small, original works of art. You can find a zine to fill just about any sort of niche you can imagine. Perhaps most importantly, zines are made by the people and for the people. They aren’t created by a mega corporation to sell you products or promote advertisements, they are created by regular people— artists— with almost no barrier to entry. Teenagers make zines in their bedrooms, professional illustrators make them in their studios, and people from diverse backgrounds make and distribute them— zine communities are very inclusive, friendly, and an overall supportive place to be.

A Brief History of Zines

To understand where these mini mags come from, we must step back in time to the beginning of public access to the printing press. Amateur printers purchased their own presses and began crafting small works centering around a specific subject or interests, especially during the Harlem Renaissance in 1920’s and 30’s New York. Many black artists during this time printed and distributed their own “little magazines” and in doing so, undermined the very systems refusing to publish their work based on prejudices.

In the late 1930’s and 40’s, sci-fi clubs created zines that explored sci-fi literature and fandoms such as “The Acolyte,” an indie publication about all things H.P. Lovecraft, or “Le Zombie,” a more general sci-fi fanzine. These were made to share thoughts and theories about sci-fi literature, creating a closer-knit community of people with the same interests from different places. Soon, these zines expanded into the realms of comics, music, and even horror.

Zines lent themselves easily to the anti-establishment ethos of the punk scene of the 70’s and 80’s, with the advent of the photocopier making the process of reproducing and distributing much more accessible.

The riot grrrl movement emerged in the early 1990’s alongside punk bands like Bikini Kill and Sleater-Kinney (plus lots more). Zines were a huge part of this subculture, which centered around feminism, the punk rock community, revolution, women’s rights, and DIY experiences. Some notable riot grrrl zines include the minizine “Riot Grrrl,” created by Molly Neuman of the band Bratmobile, Tobi Vail’s “Jigsaw,” and “Gunk” by Ramdasha Bikceem. I personally love this era of zine-making, and could talk about it for hours but I won’t do that here.

Today, zines are popular in so many subcultures and you can find a zine for just about any topic or niche. Many zines are created by hand but distributed digitally in addition to being distributed in local public and private spaces.

Zines and Gardening

So, what do DIY mini magazines have to do with gardening? Both zines and gardening have undercurrents of resistance and community— two very powerful concepts that bind us.

Accessibility | Zines can be made using any materials you already have lying around: copy paper, old magazines, paper grocery store bags, markers, anything. Gardens can be started with free seeds from a library or friend and started in a windowsill pot filled with dirt. They can be any size, grow any type of plant, and the harvest can be shared and enjoyed with others.

Inclusivity | In the 1960’s, a group of Asian-American students at San Francisco State University and UC-Berkeley came together to advocate for ethnic studies programs and Asian-American studies curriculum to be taught at their universities— a fight which they eventually won as the first Asian American studies program was a direct result of their advocacy and activism. To work towards winning this fight, the students wanted to create a newspaper focused on Asian-American issues and topics, but the university refused to fund it. In zine-culture fashion, they independently published the paper on their own using their collective personal funds. It was called “Gidra” and it ran from 1969 to 1974.

When culture at large won’t support your work, you do it yourself. Similarly, when food prices soar while quality declines, people grow gardens to feed themselves and their communities. Gardening is for EVERYONE. It doesn’t belong to people of a specific class, race, gender, or background. Anyone who wants to grow food or flowers, can. Zines were literally forged from the underground by marginalized groups: people of color, women, those who wanted their ideas heard but didn’t have a position of power or authority. This is the essence of zines. Anyone can make a zine, you don’t have to be a talented artist or writer to make an interesting zine that others will enjoy and/or learn from.

Reclaiming power within oppressive systems | Our systems are, more often than not, made to benefit those who already have power and opportunity. Marginalized groups are not prioritized and their voices aren’t as easily heard. Growing food is one of many ways that people choose to fight back against a system that doesn’t seem to prioritize our basic needs like nutritious food and human connection.

Creating zines and sharing the information inside them is another way we can reclaim power from oppressive systems. Maybe your zine about how to start seeds makes its way into the hands of someone who has been wanting to garden but wasn’t sure where to start. Perhaps a zine from a local artist inspires you to make art one afternoon. When we congregate with others working toward the same goals, we are more powerful. When we connect with others, we widen our community and produce more (and better) ideas and solutions.

Grassroots community building | Libraries often have free seed libraries, or maybe a friend or neighbor who gardens collects seeds to share. Maybe the neighbor who’s been gardening in your neighborhood since the 80’s can give you intel about growing cucumbers in a specific type of soil. We can learn from more experienced people in our communities about how to garden and grow food, share and exchange resources, and work together to meet our goals. If that experienced person is you, then share the knowledge with others, deepening bonds and building friendships.

The same is true of the zine community. Zines are made by and for everyday people and are often traded, given away for free, or sold for very little. The community is tight-knit, hyper-local, and promotes a circular economy where nothing is wasted. Everyone can contribute and benefit (much like gardening). Both also offer a sense of control through creating during turbulent times and allow you to craft your own space which is uniquely yours and/or your community’s. Both gardening and zines connect people with similar interests and hobbies— something our humanity craves.

Underground zines and gardening are about reclaiming autonomy, crafting something outside of the mainstream, and fostering a sense of community and individual agency. Whether through words and images on a page or plants in the soil, they each promote creativity, independence, and alternative, often marginalized, worldviews. Many zines emerge from countercultures, challenging mainstream media narratives and offering different viewpoints. Gardening, particularly in the context of urban gardening, guerrilla gardening, or permaculture, can be a form of resistance to industrial agriculture, food deserts, and corporate-controlled food systems. Growing your own food is an act of community sufficiency that can challenge traditional systems of control.

So, what are you waiting for? Go make a zine— or a garden— or both! Like the Chinese proverb says: “The best time to plant a tree was twenty years ago. The second-best time is now.”

I hope you will share your thoughts about this post with me and engage in conversation with myself and each other. Hold on to hope, y’all, it’s almost spring.

Cheers,

Allyson