The slow living movement was not born on modern social media platforms, but in 1980’s Italy, out of a fiery fervor for delicious food. In 1986, Carlo Petrini and friends gathered together and prepared a pasta feed, an event in which a huge meal of pasta with various sauces was cooked and shared on the Spanish Steps of Rome. Why? To protest the opening of Italy’s very first McDonald’s fast food restaurant. What an impactful demonstration, serving slow, homemade food to a community to contrast with one of fast food. Carlo Petrini founded the Slow Food Movement, which continues to gain global traction. Food is a crucial part of every culture, why make it something to “just get on with,” for the sake of convenience, when it should be an experience, an opportunity to nourish our bodies and share time with loved ones?

Moreover, why not prioritize other aspects of life that bring us happiness and togetherness the way food does? Too often, and especially lately, it feels like we don’t have any control over things happening in the world or to us. Slowing down is one small way of rebelling against a sped-up system that relies on its citizens being exhausted and overwhelmed.

The slow food movement has evolved into much more than choosing slow food over fast food. It has become a catalyst for change, prioritizing a more meaningful life. I’m going to share some statistics that may or may not be surprising, but are nevertheless concerning. Fortunately, I feel a shift, however small, is happening globally to counteract these grim statistics, so stick around for some brighter moments to follow.

*Warning for brief mention of death and suicide.

A Culture of Speed and Burnout

We are burnt out from the pace at which everything moves: communication, ads, work, commuting, trends, and media. I would argue that even those who feel they thrive in a fast-paced environment are burnt out and suffering to some degree. In Carl Honore’s “In Praise of Slowness: How a Worldwide Movement is Challenging the Cult of Speed,” the author writes about the Japanese term karoshi, which translates to “death by overwork.” For decades, Japan has seen a massive increase in early deaths caused directly or indirectly by an unhealthy culture of overwork. Cerebrovascular and cardiovascular issues, hypertension, sleep depravation leading to exhaustion, depression and anxiety leading to mental illness and, for some, suicide, have been a few results of karoshi.

“The World Health Organization (WHO) and International Labour Organization (ILO) joint unveiled that in 2021, [there were] approximately 750,000 deaths due to Karoshi syndrome globally.” https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10746923/

This obsession with overwork and speed is not exclusive to Japan, of course, and is sadly not limited to only adults. The United States, the UK, and other speed-obsessed cultures have our own problematic relationships with overwork and burnout.

A Harvard study about US students and burnout reports that “most of teens surveyed (81%) feel negative pressure in their lives, and more than half (52%) said they experience negative pressure in three of the six categories” (those categories were life plan, achievement, appearance, social life, friendship, and activism). “More than a quarter (27%) reported struggling with burnout. Pressure sometimes comes from social media, but also parents and other adults in their lives.”

Adults in the workplace are suffering too, with a 2023 APA survey reporting that “77% of workers having reported experiencing work-related stress in the last month. Further, 57% indicated experiencing negative impacts because of work-related stress that are sometimes associated with workplace burnout.” Depression, anxiety, and burnout caused by increasing social media usage affects people of all ages around the world.

These statistics are not surprising to me, but they are concerning. But what can we do to fight back? There are likely more questions than answers when trying to get to the bottom of this, but I know a good place to start. One of the most attainable options is simple— slow down.

Slow Down? You Mean Become a Lazy, Boring, Uninformed Luddite?

Slow living challenges the status quo. It begins with individuals making conscious decisions to go at their own pace, disengaging from the seemingly unavoidable wheel of consumerism and speed. It is a philosophy that does not seek to replace a sped-up culture with one of idleness, but to empower individuals to find balance in a very unbalanced world. Slowing down is not something that only people with ample money and time get to do. I know it often feels like we don’t have a choice but to participate in the accelerated way our world moves. What can we do? In our current system, we must find a way to earn money for our basic needs and to support our hobbies, travel, and enrich our lives. Consider the cost of being overworked. More than money is wasted when we speed through life and consume impulsively. Consider the time wasted trying to keep up with whatever trend or lifestyle is being advertised to us.

It’s important to find a way to decelerate and prioritize enjoying our lives. How many people do you know who have worked tirelessly for 30, 40, or 50 years, only to retire and be in too-poor physical condition to do the things they had planned for in retirement? This is a travesty, an illusion that we are sold to keep us pushing through in hopes that we will eventually make it, if only we can go faster, work harder. Slow living does not mean being lazy, idle, or forcing yourself to be physically slow. Slow living is not “a Luddite attempt to drag the whole planet back to some pre-industrial utopia” but rather, it “is made up of people who want to live better in a fast-paced, modern world,” as Carl Honoré explains in his book. He continues, saying, “the slow philosophy can be summed up in a single word: balance. Be fast when it makes sense to be fast, and be slow when slowness is called for. Seek to live at what musicians call the tempo giusto - the right speed.” If we are more centered as individuals, then we are more prepared to take action against injustices. We are more able to see injustices in the first place, and determine what we can do.

I’m not a slow-moving person. I struggle with relaxing and doing nothing. No different than others born into a new age of technology, I have been conditioned to always be searching for the next hit of dopamine and have developed a tendency to always think about what’s next. However, when I am mindful about the day-to-day, I find myself easing comfortably into slow living. I find myself feeling like I’ve been missing out on a feeling of contentment that was seemingly just out of reach before. I work a full-time job, take care of a home and small farm, have a partner, spend time with friends and family, have hobbies (arguably too many), and spend time writing and creating art. I do not live a boring, unfulfilling life of laziness. Still, I practice slow living (practice being the operative word).

Slow Living and Farming

When choosing how to describe our small farm, I stumble between definitions. Permaculture gets a glaring eye from many farmers due to an uptick in folks promoting “PDC’s,” or permaculture design courses. The courses often cost lots of money without the organizer having any real background in permaculture other than watching videos online. Organic farming has become associated with greenwashing tactics by large companies, weaponized in order to increase prices on products and sell the illusion of healthy. I have settled, for now, on describing what we do as agroecology or slow farming.

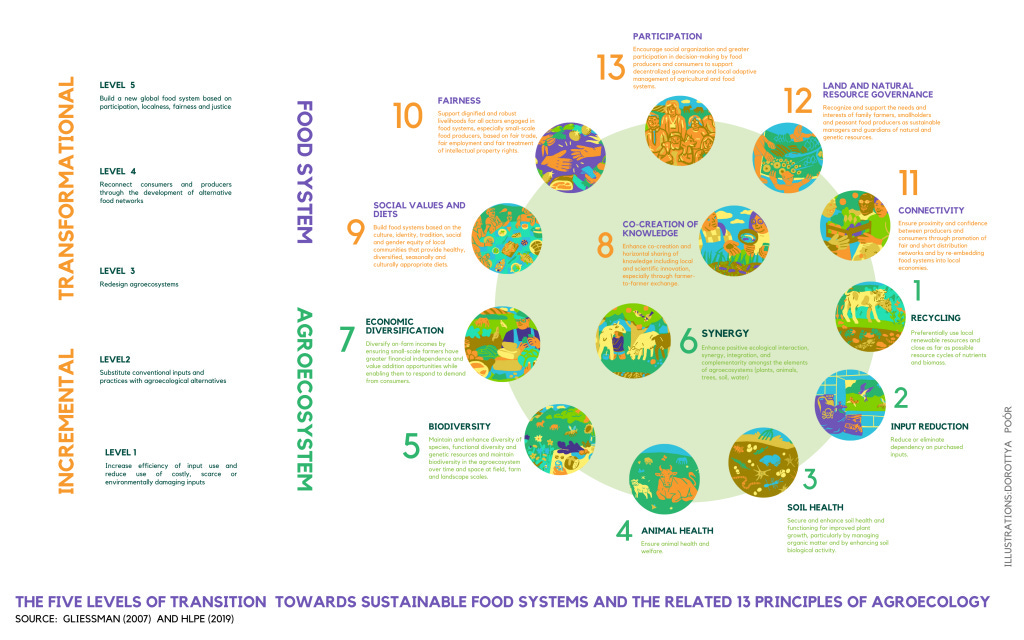

Agroecology is related to slow farming in that both focus on building beneficial relationships between agriculture and ecology, plants and people, and within communities. If you aren’t familiar with the term agroecology, it’s essentially what it sounds like: agro + ecology. It’s a set of practices and principles that integrate agriculture and ecology in ways that emphasize relationships between people, plants, animals, and food production. Slow farming uses these same practices and principles to grow food and manage land in a way that supports and prioritizes the health of ecosystems.

Slow farming describes a loose idea of using slow systems to support ecosystems, while agroecology describes a more scientific, evidence-based set of farming practices such as never using petrochemicals or synthetic fertilizers, reducing tillage, and increasing biodiversity as a few examples. Slow farming, or agroecology, maintains healthy soil in which to grow healthy food, which is prepared at home, which nourishes families, which supports healthy communities, which become resilient communities, and so it goes. Slow farming encourages slow food which encourages slow living. These slow systems can create a chain of positive consequences which create lasting change.

That is how we operate on our small farm. Here are some examples of slow processes we practice:

8 Tips for Slow Living

It isn’t always easy to choose to slow down. It is easy to get caught up in the overwhelming speed of it all. Here are some ideas and encouragement for embracing a slower life. Some of these practices have pretty much rewired my brain in only the best ways, with much time and practice. I promise you won’t be bored, dull, or idle, but more content, fulfilled, and nourished.

Embrace Slow Food

Cook from scratch more often and discover recipes you love. Building or honing your cooking skills can be a fun journey, even if you’ve never cooked before. I find it helpful to have a cookbook or two handy and have a bookmarked folder of recipes I want to try.

Make your own vegetable stock from scrap veggies. To do this, just save up your usable scraps in an airtight bag or container in the freezer until you’re ready to make broth. Then, boil those veggie scraps and add salt and seasoning to taste). Bake your own bread with just flour, salt, water, and yeast. These small things make food so much more delicious and so much more appreciated.

Small farmers tend to be slow farmers. Buy food from them as often as you can at your local farmer’s market.

Eat more fermented food. It’s very simple to make sauerkraut, kimchi, or fermented vegetables at home. All you need are clean jars and some combination of water, salt, sugar, and/or vinegar. The slow process of fermentation builds up beneficial nutrients like lactic acid which support gut health, boosting your immune system.

Eat food with loved ones when you can when you can. More importantly, cook for others when you can. Share food and share time.

Grow Food

I dedicate a large portion of this Fox Hollow project to writing about growing food, so I won’t go into too much detail here, but if you have access to sunlight, a plant pot, and water, you can grow food. Maybe you grow herbs in small pots in a windowsill or under a grow light. Perhaps you have a yard or a community garden you can make use of. Talk to experienced gardeners in your area to find out what grows well and maybe get some tips. If you cannot grow food, focus on buying your vegetables from a local farmer’s market.

Learn to Mend

Mending clothes prevents purchasing new clothing. Production of any new material, yes, even organic cotton, uses up loads of water, fuel for transportation and production, etc. It’s always better to avoid buying new if you can. If you can’t mend it, try to replace it with something second-hand.

Learning to mend not only saves you money, it is an opportunity to learn a new skill, forge a community with others who want to learn or are already experts, and mending makes you appreciate what you have even more. Mending is not limited to just clothes— learn to fix household furniture, dishes, bags, etc.

Connect with Nature

Move your body if you are able. Time outside moving around without screens is one of the best ways to regulate your nervous system and stimulate the production of happy chemicals in your brain. I once had a therapist who worked with me using EMDR, and when explaining how it works, she used the term bilateral stimulation, which means both sides of your brain are being put to work. She said it is like when you’re on a walk outside and you realize you finally have time to process complex thoughts and feelings.

Sitting or lying on the ground is another option if you aren’t able-bodied or are having a low energy day. In nice weather, I enjoy bringing a big blanket out to the yard, along with tea and my art supplies, a book, or my journal. Usually, my cat comes along and we sit for hours.

Learning about plants, birds, or wildlife is a good way to get you outside. A walk through the woods is even more engaging when you take time to observe the variety of plants and animals that you wouldn’t notice without being intentional and taking time to do so.

Keep a Commonplace Book

A commonplace book is really just an “anything” book/journal/sketchbook that you keep. It can be used to jot down recipes, ideas, thoughts, lists, drawings— anything. Use some pages to collage, write a letter you won’t send, etc. It’s a good way to be present and mindful, while also having something to look back on (like an off-screen notes app). Mine is a composition book, filled with recipes I want to try and art ideas.

Practice Creativity

Creativity isn’t something reserved for “creative types.” Creativity means giving your brain time to rest, reflect, and play. A creative practice helps you slow down and get to know yourself better. It can look a lot of different ways: picking up a new hobby like knitting, painting, sketching, carving wood, and so on. It can also look like trying new recipes, writing, photography, and obviously so much more. You don’t have to be good at it, that’s why it’s called a practice.

Embrace Boredom

Boredom is essential to creativity. If your brain is always occupied, how will it have time to come up with creative ideas? Remember being a kid and staring out the window on a car drive for thirty minutes at a time? Adult brains need time to be bored too.

One. Thing. At. A. Time.

Admittedly, this is something I have not mastered. I find myself constantly reaching for something to do with my hands while watching a movie or putting on a podcast or YouTube video while preparing food. Quietude makes my thoughts race— at first. It is uncomfortable. It is sometimes difficult to get past this and onto the stillness that I’m actually craving. It is much like meditating: As you find your thoughts wandering and becoming fast, return to your breath and remember that you are in control of your thoughts. It takes, you guessed it, practice. At times, it feels like parenting myself. “I want to turn on a podcast while I wash these dishes” and then “no, just relax and be with your thoughts.” Followed by, “but I don’t want to, it’s hard,” then “yes, but it will get easier with practice.”

As Lao Tzu wrote: “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.”

“Fast and Slow do more than just describe a rate of change. They are shorthand for ways of being, or philosophies of life. Fast is busy, controlling, aggressive, hurried, analytical, stressed, superficial, impatient, active, quantity-over-quality. Slow is the opposite: calm, careful, receptive, still, intuitive, unhurried, patient, reflective, quality-over-quantity. It is about making real and meaningful connections - with people, culture, work, food, everything.” ― Carl Honoré, In Praise of Slow: How a Worldwide Movement is Challenging the Cult of Speed

With defiance (and love),

Allyson

Oh I love the idea of a commonplace notebook. I always feel like everything needs to have a specific purpose (recipe book, writing prompt book, etc.) and then end up with a bunch of random, quarter-filled books I don't reread because there are too many of them.

Also can you share your sauerkraut / kimchi tips? We have so much cabbage and I looked up a recipe and like you said, it looks so easy! But I'm still afraid to mess it up!